Nearly 10 years ago, the city of Portland first committed to a Vision Zero plan, setting a goal to eliminate all traffic crash fatalities and serious injuries on Portland’s streets by 2025. That year, the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) reported 35 traffic crash deaths in Portland. City officials said at the time they didn’t take the rising traffic crash death toll lightly, and were strongly dedicated to the Vision Zero goals.

It’s now 2024, and traffic crash deaths in Portland are at a 30-year high. According to PBOT’s report on deadly traffic crashes for 2023, 69 people died on Portland’s streets last year. Though fatal crashes have been rising in Portland over the past several years, 2023 was the deadliest year in recent history. This isn’t how the trend is supposed to go—especially not in a city committed to Vision Zero.

Yesterday, Portland City Council accepted last year’s deadly crash report and adopted the first update to the Vision Zero Action Plan since 2019. Right off the bat, PBOT leaders got ahead of the elephant-in-the-room question on everyone’s minds: Considering how traffic crash deaths are rising so significantly, is Vision Zero working?

PBOT’s message is that Vision Zero works if you work it.

“Where we have invested, we have had success,” PBOT Commissioner Mingus Mapps said at the meeting.

But transportation advocates–who have tried for years to get city officials to take this matter seriously–remain skeptical, at best, about the city’s commitment to Vision Zero and a “safe systems” approach to traffic safety. Many people, having seen or experienced the devastation resulting from preventable traffic crash deaths, no longer believe PBOT leaders are doing all they can to stop this scourge.

“There is no question that Portland's Vision Zero Program has been an abject failure. Given its abysmal track record, it is reasonable to conclude that it will continue to be a failure,” Sarah Risser, a local transportation safety activist, wrote in public testimony to City Council ahead of the April 17 meeting. “I am under the very strong impression that Portland's Vision Zero program exists to signal a desire for zero road fatalities and, by doing so, allow leaders to evade the hard work that is needed to realize its goal.”

Deadly crashes in 2023

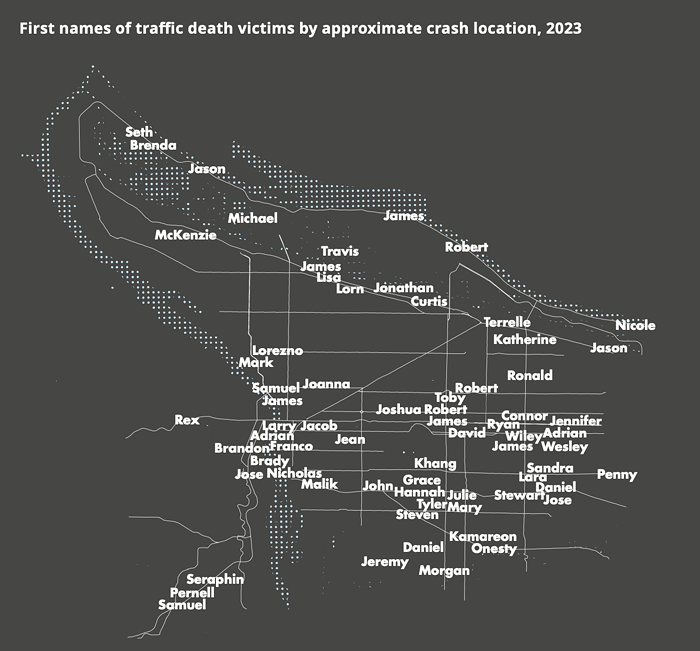

Many of the details of the 2023 Vision Zero fatalities report will be familiar to those who have followed the increased deadly crashes in Portland over the past few years. But before examining trends, the report points out the 69 people who died on Portland’s streets last year are more than mere statistics.

“Those killed by traffic violence this year were children, siblings, parents, aunts and uncles, grandparents, neighbors, and friends,” the report states. “Our city mourns those lost. We can and must do better.”

The majority of people who died in traffic crashes in 2023 were in a motor vehicle (32 people), and 11 people were on motorcycles. Another 24 people were classified by PBOT as pedestrians, which includes walking as well as using a mobility device, skateboard, or e-scooter, and two were on bicycles.

While deaths occurred all over the city, the majority were concentrated in areas that have historically been the site of the most crashes. About 75 percent of traffic deaths occurred on Portland’s busiest streets, which make up the city’s “high crash network,” and many of those were in East Portland. Crashes are more likely to occur on wide streets with four or more travel lanes—it takes longer to cross these streets while walking or on a bike, and drivers are more likely to speed on wide roadways. Traffic violence also disproportionately impacts Portland’s Black community.

The traffic crash report highlights “persistent trends” that have endured over several years related to traffic fatalities. These include speeding (the report states 87 percent of traffic deaths happen on streets with speed limits of 30 miles per hour or more, when those make up only 8 percent of Portland’s streets), increased pedestrian deaths, deaths occurring in low-light conditions (at night or early in the morning), and impaired driving.

Another trend is the disproportionate impact of traffic violence on homeless people. In 2021, the Portland Police Bureau started tracking the housing status of people who died in crashes. Last year, half of the pedestrians who were killed were identified as homeless.

“These statistics speak to the extreme risks of persistent exposure to traffic, often on high-speed streets,” the report states.

PBOT leaders told the council that, while they recognize the rising traffic violence crisis, it’s important to highlight some of the recent progress as well—further emphasizing the message that the Vision Zero program is successful when PBOT is able to fully invest in it.

Dana Dickman, PBOT’s traffic safety section manager, said Vision Zero “is working when we have been able to make changes on our streets.”

“If you see a street that hasn’t been changed at all in 10 years, we’re not going to expect to see different safety outcomes than we’ve had over the last few decades,” Dickman said.

The 2023-2025 Vision Zero update acknowledges the “brutal fact” that traffic crash deaths have increased significantly since the first action plan was adopted in December 2016. But it also says PBOT has accomplished several major safety gains.

Dickman cited a few specific examples of recent PBOT projects she said have made a positive impact on safety, including on Southeast Hawthorne Boulevard, Southwest Beaverton Hillsdale Highway, and outer Southeast Division Street.

Not all the streets in Portland are within PBOT’s jurisdiction. Data show 25 percent of traffic crash deaths in 2023 took place on streets operated by the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), like Southeast Powell Boulevard and North Lombard Street, where the city is limited in its ability to make infrastructure changes.

But PBOT Director Millicent Williams said the state agency is also committed to Vision Zero on its streets.

“There is significant work that ODOT is doing,” Williams said. “They are committed to ensuring we’re creating safety across the network that we both share and that they are responsible for managing independently.”

Advocates push for more urgent action

PBOT’s messaging was disappointing to transportation safety advocates who hoped the bureau would take more responsibility for its shortcomings. Considering the marked rise in traffic crash deaths, they believe the city needs to commit to taking much more radical action if leaders are serious about turning things around.

“For years, advocates have been sounding the alarm on the worsening epidemic of traffic violence in our community and proposing solutions which have been ignored by the City Council,” Sarah Iannarone, executive director of nonprofit The Street Trust, said in a press release. “Of course the problem continues to worsen.”

The Street Trust proposed several actionable steps the city could take to combat traffic crash deaths. The recommendations included:

- Limiting speed limits to 20 mph on the entire high crash network;

- “Aggressively accelerate installing infrastructure” including banning car parking within 20 feet of intersections (a concept known as “daylighting” intersections);

- Investing in more automated traffic enforcement, and supporting efforts to fund safety projects on state-owned roads in next year’s legislative session

Overall, Portland transportation advocates want to see the city do better. But history shows they shouldn’t hold their breath.

“Our organization wants to be excited and supportive. But I also want to be really honest, the reality of our streets is not a surprise. We've seen the numbers go up and up and up every year for many years,” Zachary Lauritzen, the interim executive director at transportation safety nonprofit Oregon Walks, said.

Lauritzen also asked the city to get on board with upcoming opportunities to improve safety on the streets, including forthcoming plans to reconstruct Northeast Sandy Boulevard and 82nd Avenue.

“If today turns out to be an inflection point in change, we will be thrilled. But as an advocate, I want to note we’ve been here before,” Lauritzen continued. “We’ve been at somber events, we’ve been at memorials where we say the work is important…that loss of life is terrible. And yet, here we are again.”